Being a history nerd, I’ve always enjoyed “on this day in history” facts. There’s something so fun about realizing on this ordinary date in my life, something world-altering could’ve been happening in the past. So today, January 16th, I’m sharing one of those moments with you: on this day in 1847, John C. Frémont, a man whose name frequents the history of the American West, was appointed Military Governor of the California Territory by Commodore Robert F. Stockton.

Now, typically, I’m not the biggest fan of biographies. They can feel like a dry slog of names and dates – while fascinating and informative, not the most fun way to consume history. That being said, Frémont is a figure that was so peripherally influential across the Intermountain West that I had to give in. His story is ripe with exploration, war, politics, science, and controversy, often all at the same time. He’s appeared as a side character in some of my other posts, but today he takes center stage as Modern Major-General (after all, like Major-General Stanley in Pirates of Penzance, Frémont had a wide range of knowledge, but perhaps too little of military tactics) as we ask: who was this guy anyway?

We’ll pick up Frémont’s story in his twenties, around the 1830s. Even prior to this time in his life, he had a reputation as a rebellious child with a taste for adventure… and possibly mule…(iykyk)? That restlessness in his youth turned into a career when he became second lieutenant for the U.S. Army Corps of Topographical Engineers. His early work involved surveying routes for the Charleston, Louisville, and Cincinnati Railroad Project, an attempt to link the Ohio River to the Atlantic by cutting through the Appalachian Mountains.

Surveying might sound a bit boring to us now, but it sharpened Frémont’s skills that would later define his life. While working as a surveyor, and later as an assistant to the explorer Joseph Nicolett, he became proficient in topography, astronomy, geography, geology, and in the description of fauna, flora, soil, and water resources – he probably knew his way around the scientific names of beings animalculous: In short, in matters vegetable, animal, and mineral (hello again, Major-General Stanley).

A few years later, Frémont’s career path changed thanks to his new father-in-law, Senator Thomas Hart Benton of Missouri (also known as “Old Bullion.” What a nickname!). Benton was one of the loudest champions of Manifest Destiny (the belief that the United States was destined to expand westward), and under his influence, Congress pushed for national surveys of things like the Oregon Trail, the Great Basin, and routes through the Sierra Nevada to California. Thanks to his backing, Frémont secured leadership, funding, and patronage for three expeditions. It’s no stretch to say that without his father-in-law’s help, Frémont wouldn’t be the national figure he became.

Following in the footsteps of names like Lewis and Clark, Zebulon Pike, Peter Skene Ogden, and Jedidiah Smith, John C. Frémont joined the ranks of great western explorers. What set him apart wasn’t only where he went, but how well he documented it. His documents were readable, his scientific observations thorough, and his maps extremely useful, no doubt thanks to his earlier career as railroad surveyor. Along the way, Frémont was assisted by legendary mountain man and guide Kit Carson and his friend Lucien Maxwell, names that – to me – feel inseparable from the mythology of the American frontier.

By 1846, a series of maps based on his expeditions had been published, depicting the entire length of the Oregon Trail. These maps became essential guides for thousands of emigrants heading west.

After his expeditions, Frémont’s career took another turn, straight into the military conflict during the Mexican-American War. He led the California Battalion and helped capture Santa Barbara, the Presidio, and parts of Los Angeles. At some point during this time, Frémont began signing his letters “Military Commander of the U.S. Forces in California,” a bold move and a lengthy signoff.

He also signed the Treaty of Cahuenga, effectively ending the war in most of California. Around this same time, General Stephen F. Kearny, fresh from conquering New Mexico (read about it here!), ordered Frémont to join his dragoons. Frémont refused, believing he was under the authority of Commodore Robert Stockton.

That brings us back to January 16th, 1847, when Stockton appointed Frémont the Military Governor of the California Territory. Unfortunately for Frémont, a month later Kearny was informed that he was the military governor. Kearney’s authority ultimately carried more weight, and Frémont soon found himself court-martialed.

He was charged with mutiny, disobedience of orders, and assumption of powers. While acquitted of mutiny, he was convicted of disobedience towards a superior officer and military misconduct. President James K. Polk softened the blow by reducing the sentence to dishonorable discharge and reinstating him in the Army, partly to appease Senator Benton, who was convinced his son-in-law had been wronged.

After this episode, Frémont returned to what he knew best: exploring. On his fourth expedition, he hired Richens “Uncle Dick” Wooten (another name we come across a lot!) as a guide through the Sangre de Cristo Mountains. This journey was made infamous for its particularly bleak mule-laden Christmas breakfast..… a true low point, even by frontier standards (learn more about that Christmas here). The party eventually staggered into Taos two months later to recuperate before Frémont made his way back to California.

Frémont’s next act was political. He served briefly as one of California’s first U.S. senators from 1850 to 1851. In 1856 he ran for president as the first-ever Republican Party candidate, ultimately losing to James Buchanan.

When the Civil War erupted a few years later, President Abraham Lincoln appointed Frémont major general and placed him in command of the Department of the West. Once again, controversy followed. Without consulting Lincoln, Frémont declared martial law in Missouri, ordered confiscation of rebel property, and proclaimed the emancipation of slaves belonging to secessionists. Lincoln, fearing Missouri would tip to the Confederate side, publicly revoked the emancipation clause. Frémont later faced Confederate General Thomas “Stonewall” Jackson at the Battle of Cross Keys in 1862, but failed to stop Jackson’s retreat. Shortly thereafter, Frémont requested relief from command and never again held a field command.

Frémont wasn’t done with public service though. Under President Rutherford B. Hayes, he was appointed governor of the Arizona Territory in 1878, though Frémont spent little time there and eventually resigned rather than return in person. In April 1890, he was re-appointed major general and placed on the Army’s retired list. Three months later, he died of peritonitis (the inflammation of the inner lining of the abdomen).

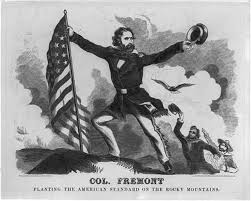

John C. Frémont’s legacy is often viewed as polarizing. He played a major role in opening the American West to settlement and was widely celebrated as a national hero, earning the nickname “The Pathfinder.” His maps, reports, and scientific documentation helped greatly in guiding emigrants westward. He symbolically claimed the West for the United States by planting an American flag atop the Rocky Mountains on his first expedition.

Scientifically, his impact was huge as well. Frémont documented over 150 new plant species and 19 new genera. Numerous plants bear his name today, including the Frémont cottonwood, Frémont Barberry, and the genus Fremontodendron.

And yet, he was also famously difficult. Abraham Lincoln once remarked that Frémont “isolates himself, and allows nobody to see him; and by which he does not know what is going on in the very matter he is dealing with.” Maybe he should’ve stuck to exploring…..

Scientist, explorer, politician, and perpetual attractor of controversy, John C. Frémont embodies the contradictions of America’s westward expansion. And on this day in history, it’s worth remembering how complicated the life of “The Pathfinder” really was.

Take Heart!

Mountain Girl

Leave a comment