This week’s blog is on a heavier topic than usual, but an important one nonetheless.

In the early 20th century, coal mining was booming in Colorado. As mining does, the work attracted many eager to do the job, locals and immigrants alike. A majority of those who worked the mines lived with their families in the company towns, and as the miners weren’t paid well – only being paid for coal brought in, not other labor like laying track and the developing of the mines, known as “dead work” – living in a company house and shopping at a company store made the most sense (these types of towns were also used during the Dust Bowl, when many fled to California and worked various crop fields). This not only benefitted the workers, but the mining companies as well; money paid to its employees came back into their pockets, and any labor unrest was often contained.

In addition to harsh working conditions, working in a mine could be deadly. In 1910, over 400 miners died in Colorado due to work related incidents. This, combined with forced overtime, lack of pay for “dead work,” and many other factors, lead to the Strike of 1913 and the beginning of the Colorado Coalfield War. Perhaps instigated by Mary Harris (better known as Mother Jones), a union organizer who helped lead many labor strikes, who had come to Trinidad to lead the United Mine Workers of America in a strike against the Colorado Fuel and Iron Company (CF&I), then owned by John Rockefeller Jr. and the largest employer in the state at the time. Similarly to the Santa Fe Ring, CF&I depended on the immigrants’ inability to speak or understand English, as well as ignorance of rights. The call to action for the Strike of 1913 read:

“All mineworkers are hereby notified that a strike of all the coal miners and coke oven workers in Colorado will begin on Tuesday, September 23, 1913 … We are striking for improved conditions, better wages, and union recognition. We are sure to win.”

Throughout the fall and winter of 1913, and leading into the spring of 1914, many strikes were being held, and those striking could no longer live in the company towns. As a result, tent cities began forming, one of which was in Ludlow, Colorado (now a ghost town just north of Trinidad). In the spring of 1914, after over 6 months of striking, tensions were rising. The Colorado National Guard had established their presence to keep strikers at bay, but occasionally outside strike-breakers would be hired by CF&I who would work without union approval and terrorize the tent cities. Many families in these tent cities dug holes in the ground for places to hide.

Rockefeller realized the extremity of the situation and said to a Congressional committee just 2 weeks before the massacre, “There is just one thing that can be done to settle this strike, and that is to unionize the camps, and our interest in labor is so profound and we believe so sincerely that that interest demands that the camps shall be open camps, that we expect to stand by the officers at any cost.” Unfortunately, events were already set in motion by the blazing tensions between the militia and strikers.

On April 20th, 1914, the leader of the Ludlow tent city, Louis Tikas, went to Major Patrick Hamrock, the head of the National Guard in the area. It’s unclear if Tikas was attacked during the meeting or during the fight itself, but he was ultimately killed. The National Guard (some of which were hired guns in National Guard uniform) descended on Ludlow, and miners took shelter in a nearby arroyo behind railroad tracks, attempting to draw attention, and gunfire, away from the families still in the tent city. Many women and children took shelter in the pits that had been dug. The uniformed strike breakers moved into the tent city and began to set tents aflame. The camp was destroyed, and women and children had been trapped due to the fire, ultimately dying as a result.

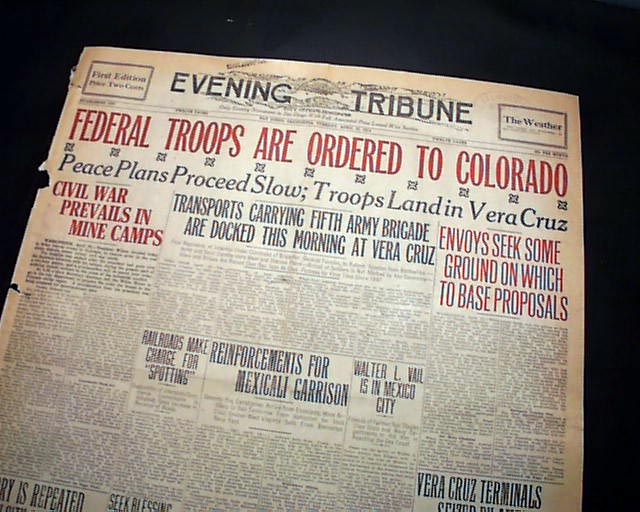

Following the massacre, the 10 Day War began, and miners took revenge on the companies, killing national guardsmen and strike breakers. President Woodrow Wilson eventually called on the US Army to end the violence. After all was said and done, Rockefeller’s image was in need of serious repair, so in addition to hiring a public relations team, he also met with none other than Mother Jones herself during his trip to Colorado during the introduction of new mining reforms.

The deaths of women and children shocked the nation and started an outcry about workers’ rights and labor disputes. So, while the goals of the strikes in Ludlow were not realized at the time, the legacy of the massacre went on to pave the way for future labor reforms.

This was a pretty rough topic, so I’ll just leave you with a quote of Kierkegaard’s: “Life must be lived forward, but it can only be understood backward.”

Mountain Girl

Leave a comment